Armed Resistance and the Struggle for Self-Determination

A Militant Organizer’s Perspective

Self-determination, the right of peoples to freely determine their political, economic, and cultural destiny, is a fundamental human right. Yet, for many oppressed communities, this right is denied through colonialism, occupation, and systemic violence. When peaceful avenues for liberation are systematically crushed, armed resistance emerges not as a choice but as a necessity. This article explores the role of armed struggle in the fight for self-determination, drawing on historical and contemporary movements in Palestine, Rojava, Chiapas, Argentina, Chile, and the Black liberation movement in the US. From the perspective of a militant organizer, it argues that armed resistance is a legitimate and often indispensable tool in dismantling structures of oppression.

The Necessity of Resistance

Self-determination cannot exist under the boot of occupation or apartheid. When dialogue is silenced, protests met with bullets, and political leaders imprisoned, oppressed peoples face a distinct reality: submit or resist. Frantz Fanon, in The Wretched of the Earth, proposes that violence, while a tragic recourse, becomes a transformative force for the colonized, breaking the psychological and physical chains of subjugation. Armed resistance, in this context, is not mere aggression but a form of self-defense and a catalyst for asserting agency.

The necessity of armed resistance is rooted in the fundamental imbalance of power that defines occupation and apartheid. Oppressive systems are not static; they are engines of violence designed to perpetuate control through fear, fragmentation, and erasure. When states criminalize dissent by banning protests, censoring speech, and imprisoning organizers, they reveal their intolerance not just for rebellion, but for existence outside their terms. Under such conditions, the choice to resist violently is not a rejection of peace, but a rejection of the oppressor’s unilateral monopoly on violence. As revolutionary theorist George Jackson wrote, “The concept of nonviolence is a false ideal. It presupposes the existence of compassion and a sense of justice on the part of one’s adversary.” When these are absent, as they are in colonial and racial-capitalist projects, the oppressed are left with two options: annihilation or rebellion.

This dynamic is further complicated by the structural nature of state violence, which operates not only through overt force but through the slow, bureaucratic suffocation of communities. Settler-colonial regimes, for example, weaponize land theft, resource extraction, and legal systems to dismantle collective identity and sovereignty. Indigenous peoples globally face cultural genocide when their languages, rituals, and ties to the land are severed by state policy. In these contexts, armed resistance becomes a means of preservation—a refusal to let one’s history, ecology, and future be dissolved into the oppressor’s narrative. It is a declaration that some lines cannot be crossed, some truths cannot be buried. Violence alone, when wielded by the oppressed, can shatter the psychological paralysis imposed by the colonizer. The act of fighting back, even at great cost, ruptures the myth of invincibility that sustains oppressive regimes, proving that their power is neither absolute nor eternal.

Case Studies in Revolutionary Struggle

1. Palestine: Resistance Against Settler Colonialism

The Palestinian struggle, spanning decades, epitomizes the fight against settler colonialism. From the PLO’s guerrilla warfare in the 1960s to Hamas’s confrontations today, armed resistance has been a response to land confiscation, checkpoints, and massacres. While criticized as terrorism by “israel” and its allies, these actions are rooted in the right to resist occupation. The Great March of Return (2018–2019), though non-violent, saw over 200 protesters killed by “israeli” forces—underscoring the reality that even unarmed dissent is met with lethal force.

The Palestinian armed struggle cannot be disentangled from the historical continuum of zionist settler colonialism, which has sought to displace and replace Indigenous Palestinians since the Nakba (Catastrophe) of 1948. From the massacre of Deir Yassin to the ongoing siege of Gaza, “israel’s” project has relied on a logic of elimination—demographic, spatial, and cultural. In response, Palestinian resistance factions, from the PFLP to Islamic Jihad, have employed diverse tactics to disrupt this colonial calculus. While Western media often reduces these groups to “militants” or “terrorists,” their emergence is inseparable from the conditions of apartheid: home demolitions, arbitrary detention, and the denial of basic rights like water and movement. Even symbolic acts of defiance, such as the 2021 Unity Intifada, where Palestinians in occupied territories, Gaza, and within “israel’s” borders rose up in a rare coordinated wave of protests and were met with state violence, including the bombing of Gaza and mass arrests. This underscores a brutal truth: whether through stones or rockets, “israel’s” machinery of repression treats all resistance as existential threats to its settler project.

Critics who condemn Palestinian armed resistance as “counterproductive” often ignore the systemic erasure of alternatives. The Oslo Accords, publicized as a pathway to peace, instead entrenched occupation, expanding settlements and fragmenting Palestinian land into disconnected states. When diplomacy becomes a tool of pacification, armed struggle reclaims political urgency. Resistance is not a policy choice; it is the natural reaction of a people confronting annihilation. The rockets launched from Gaza, often dismissed as futile, are not weapons of war but symbols of refusal and a demand to be seen as human beings entitled to dignity and sovereignty. In this imbalance, armed struggle becomes both a material and moral necessity: a means of survival and a refusal to let the world look away.

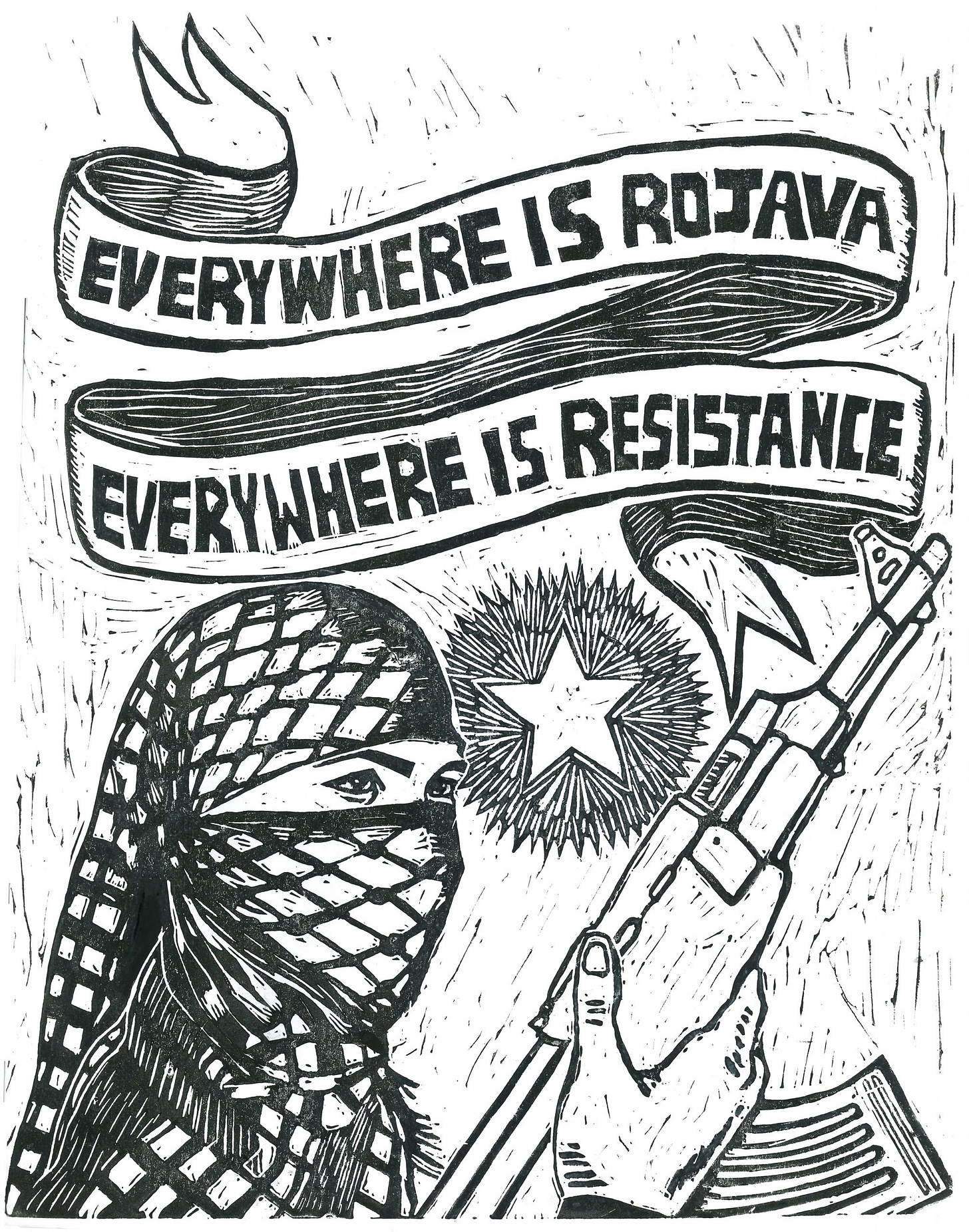

2. Rojava: Revolution in the Rubble

In northern Syria, the Kurdish-led Rojava Revolution combines armed resistance with radical democracy. The YPJ/YPG militias, fighting ISIS and Turkish invasions, defend a society built on women’s liberation, ethnic pluralism, and ecological sustainability. Their struggle illustrates how armed defense can protect revolutionary social projects from annihilation, creating space for autonomous governance despite relentless attacks.

The Rojava Revolution’s armed resistance is inseparable from its radical reimagining of society. Rooted in the political philosophy of Abdullah Öcalan and the principles of democratic confederalism, Rojava’s project rejects the nation-state model in favor of decentralized, grassroots governance. Local communes and councils, led by women, youth, and diverse ethnic groups like Arabs, Assyrians, and Yazidis, operate alongside the YPJ/YPG militias, embodying the revolution’s ethos that “defense is not just military, but social.” This dual approach has allowed Rojava to withstand not only ISIS’s genocidal campaigns, such as the 2014 siege of Kobanî, but also NATO member Turkey’s invasions, which have displaced hundreds of thousands and targeted critical infrastructure like water supplies and farmland. The YPJ/YPG’s success in liberating territories from ISIS, often at immense human cost, was not merely a military victory but a defense of Rojava’s experimental social contract; one where women’s assemblies veto patriarchal laws, ecological cooperatives replant war-scarred landscapes, and multilingual education dismantles decades of Arab nationalist erasure.

Critics who dismiss Rojava’s armed resistance as “utopian” or “unrealistic” overlook the geopolitical siege it navigates. While the Autonomous Administration avoids sectarian agendas, its existence threatens regional powers, like Turkey, who view its anti-capitalist, pluralist model as a destabilizing force. Turkey’s drone strikes on Kurdish leaders and its proxies’ ethnic cleansing of Afrin exemplify the existential stakes. Yet, Rojava persists, precisely because its fighters understand that surrendering arms would mean surrendering the revolution itself. Rojava resistance fighters are not fighting just to destroy ISIS, but to prove another world is possible. In this way, Rojava’s resistance transcends mere survival; it becomes a living blueprint for how armed struggle can safeguard liberation, not as an end goal, but as the foundation for building a freer society.

3. Zapatistas: From Arms to Autonomy

Mexico’s Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) launched an armed uprising in 1994, declaring “¡Ya Basta!” against neoliberalism. While their initial insurrection was brief, it forced the world to confront Indigenous marginalization. Today, the Zapatistas focus on building autonomous municipalities, proving that armed resistance can shift power dynamics, enabling non-violent self-organization.

The Zapatistas’ armed uprising on January 1, 1994—timed to coincide with the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)—was a calculated rupture against centuries of Indigenous erasure and neoliberal dispossession. By seizing towns in Chiapas and declaring war on the Mexican state, the EZLN transformed Indigenous struggles from localized grievances into a global symbol of anti-capitalist resistance. Though their military engagement lasted only 12 days, it exposed the violence embedded in Mexico’s “peaceful” transition to neoliberalism, which privatized communal lands and dismantled constitutional protections for Indigenous peoples. The rebellion’s brilliance lay in its duality: the masked guerrillas wielded rifles not to conquer territory, but to amplify the voices of Mayan communities through communiqués penned by Subcomandante Marcos. This synthesis of armed theater and political poetry forced the world to reckon with a simple truth, as Marcos wrote: “We are the product of 500 years of resistance.”

Today, the Zapatistas’ autonomous municipalities, governed through mandar obedeciendo (“leading by obeying”), demonstrate how armed resistance can create fertile ground for radical peace. In over 40 caracoles (autonomous zones), Indigenous councils manage education, healthcare, and justice systems rooted in collectivism and ecological stewardship. Women, once excluded from public life, now hold half of all leadership roles. These projects thrive not because the Mexican state permits them, but because the EZLN’s lingering presence—a disciplined, though rarely deployed, militia—deters state and paramilitary incursions. Their resistance has evolved into what they call “a war of resistance,” where building schools and planting corn are acts of defiance as potent as any bullet. As the Zapatistas assert, they are not seeking to take power. They are seeking to dissolve it.

4. Southern Cone: Fighting State Terror

In 1970s Argentina and Chile, military juntas disappeared tens of thousands. Groups like the Montoneros (Argentina) and MIR (Chile) took up arms against dictatorships, targeting symbols of state terror. Though ultimately crushed, their resistance preserved a legacy of defiance, inspiring future movements to confront impunity.

The armed resistance movements in Argentina and Chile emerged as desperate counterattacks against regimes that had weaponized the state itself into a machine of terror. In Argentina, the Montoneros, a coalition of left-Peronist youth, workers, and intellectuals, sought to expose the junta’s claims of “order” and “Christian morality” by targeting military officers, police torturers, and corporate elites complicit in the dictatorship’s economic plunder. Their 1975 assassination of General Juan José Valle, a key architect of the Dirty War, was not just a tactical strike but a symbolic unmasking of the junta’s hypocrisy. Similarly, Chile’s Revolutionary Left Movement (MIR), founded years before Pinochet’s coup, anticipated fascism’s rise and built clandestine networks to resist it. After the 1973 overthrow of Salvador Allende, MIR militants executed daring operations—raiding armories, bombing secret police headquarters—to disrupt the regime’s illusion of total control. Both groups understood that in the face of desaparecidos (the “disappeared”), concentration camps like Villa Grimaldi, and US-backed Operation Condor, passive resistance meant collective death.

Though outgunned and infiltrated by state intelligence, these movements ruptured the myth of invincibility cultivated by the juntas. The Montoneros’ 1970 kidnapping and execution of former dictator Pedro Aramburu, a figure tied to prior anti-worker massacres, signaled that even the most untouchable elites could be held accountable. In Chile, MIR’s continued underground resistance—distributing pamphlets, sabotaging infrastructure—proved that Pinochet’s terror could not extinguish dissent. Their struggles, though militarily defeated, laid groundwork for later movements: Argentina’s Madres de Plaza de Mayo, who turned maternal grief into a global human rights campaign, and Chile’s arpilleras (quilting circles), who stitched subversive art documenting state crimes. The armed resistance’s greatest legacy was its refusal to let fear paralyze collective memory—a lesson that resonates today, as new generations across the Southern Cone mobilize against neoliberalism’s resurrected ghosts.

5. Black Liberation in the US: Panthers and Beyond

The Black Panther Party (BPP) redefined armed resistance as community defense—patrolling neighborhoods with firearms to counter police brutality. While COINTELPRO dismantled the BPP, their ethos of self-defense persists. Figures like Assata Shakur and movements like the Black Liberation Army highlight the intersection of racial capitalism and state violence, affirming that for the colonized, survival itself is resistance.

The Black Panther Party’s armed resistance was inextricably linked to their vision of revolutionary community care. Beyond patrolling neighborhoods with shotguns to monitor police, the BPP built parallel institutions that directly addressed the violence of racial capitalism. Their Free Breakfast for Children Program, launched in 1969, fed thousands of Black youth daily, while medical clinics and liberation schools provided healthcare and education stripped away by systemic neglect. These programs were not charity but acts of political warfare—proof that Black communities could sustain themselves outside the grip of a state that criminalized their existence. The Panthers’ fusion of armed self-defense and mutual aid exposed the contradictions of a government that spent millions militarizing police while denying basic resources to Black neighborhoods. Their rifles were symbols of defiance, but their survival programs laid bare the deeper violence of poverty and segregation.

The state’s brutal response to the Panthers—COINTELPRO’s assassinations, frame-ups, and psychological warfare—sparked a broader radicalization. Groups like the Black Liberation Army (BLA) emerged from the ashes, adopting tactics to combat what they saw as a genocidal war on Black life. Figures like Assata Shakur, hunted and imprisoned for her alleged role in armed actions, became emblems of resilience. In her autobiography, Shakur reframed “criminality” as resistance: “Nobody in the world, nobody in history, has ever gotten their freedom by appealing to the moral sense of the people who were oppressing them.”

Today, the Panthers’ legacy reverberates in movements like Black Lives Matter, which, while predominantly nonviolent, inherits their critique of policing as a tool of racial control. From the uprisings in Ferguson to the armed community patrols in Atlanta’s Cop City protests, the demand remains the same: an end to state violence, by any means necessary. We must not fear militancy, as the conditions we face make it necessary for the people to be militant.

Addressing Criticisms

Critics argue that armed struggle perpetuates cycles of violence or harms civilians. Yet, these critiques often ignore the asymmetry of power: oppressed groups face state militaries, drones, and economic blockades. The violence of the oppressed is never equivalent to the systemic violence of the oppressor. Moreover, movements like Rojava and the Zapatistas demonstrate that armed resistance can coexist with ethical frameworks, minimizing civilian harm while challenging militarism.

The moral equivalence often drawn between state violence and revolutionary violence obscures a critical distinction: intent and accountability. Oppressive systems deploy violence to maintain hierarchies of exploitation, whereas armed resistance seeks to dismantle those hierarchies in pursuit of collective liberation. Critics who equate the two ignore how state violence is structural—embedded in laws, economies, and institutions—while resistance violence is reactive, a rupture against that very structure. For instance, during South Africa’s anti-apartheid struggle, the ANC’s armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe, targeted infrastructure, not civilians, to avoid the indiscriminate brutality of the apartheid regime. To condemn armed resistance as “immoral” without contextualizing its roots in systemic violence is to side with the oppressor’s monopoly on determining what constitutes “acceptable” resistance. As Angela Davis reminds us, “Radical simply means ‘grasping things at the root,’” and the root of armed struggle is not bloodlust, but the unyielding will to live free.

Liberation as the Horizon

For the militant organizer, armed resistance is neither romantic nor desired—it is a grim necessity imposed by unrelenting oppression. It is a tool among many, wielded when all else fails, to carve out space for liberation. From Palestine to Rojava, these struggles teach us that resistance is multifaceted: it is the rifle, the pen, the protest, and the dream of a free society. As international solidarity activists, our role is not to police the methods of the oppressed but to amplify their demands for justice. In the words of Malcolm X, “We declare our right on this earth to be a human being, to be respected as a human being, in this society, on this earth, in this day, which we intend to bring into existence by any means necessary.”

The path to liberation is paved with the legacies of those who refused to kneel—from the maroon colonies of escaped slaves to the urban guerrillas of today’s metropoles. While the forms of resistance evolve, the core truth remains: oppressed peoples do not choose violence; they inherit it from the structures that cage them. Solidarity, then, demands more than passive empathy—it requires material support for those resisting annihilation, whether through divestment from apartheid economies, direct aid to besieged communities, or confronting the imperialist powers that arm oppressive regimes.

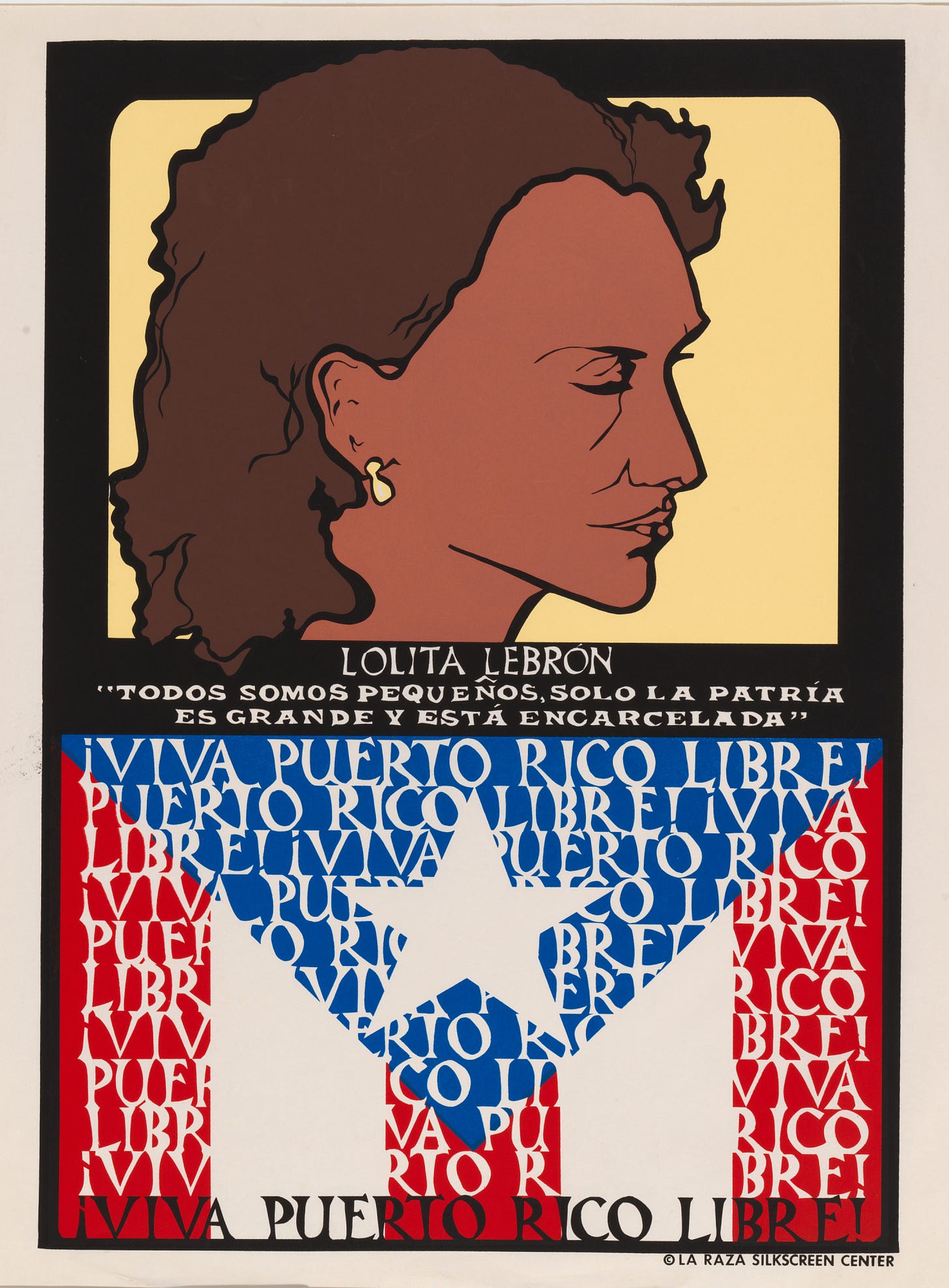

As Puerto Rican revolutionary Lolita Lebrón declared before her imprisonment for leading an armed attack on the US Congress in 1954, “I did not come to kill anyone. I came to die for Puerto Rico.” Her words echo across generations, a reminder that armed struggle is not a fetish but a testament to the unbreakable will to live—and die—free. The horizon of liberation is not a distant utopia; it is forged daily in the collective refusal to accept bondage, by any means history demands.

Shared your article to Revolutionary News Today which I am a contributor to. Very well thought out. The question is when will the working class and the American people be willing to take up arms? I am afraid it will have to be when the ruling class kills hundreds and thousands of us. As you know the revolution has to go through stages. And we can't skip them. Thanks for the article as it is really thought provoking. https://substack.com/@revolutionarynewstoday

The RNT Collective enjoyed your Voice and wish to hear more !